Honoring Kentucky’s tradition of reform and commitment to student achievement, the Committee sought first to better understand the opposing viewpoints and to identify a common definition of charter schools. The viewpoints ranged from a deeply held belief that the public education system should allow for more choice by parents to an equally strong belief that public investment should be used to strengthen the traditional system of education in an effort to serve students better. The common thread definition for all charters is that they accept responsibility for student outcomes in exchange for freedom to innovate and public funding.

We worked through the fall to gather unbiased information on the organizational and operational elements of charter schools. We took a close look at charters in Louisiana, and New Orleans specifically where public charters were used to quickly get a system of education back up and running in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina. We engaged the National Council of State Legislatures to provide a landscape of charters across the country and to help us understand the funding mechanism for public charters; the National Governor’s Association to help us understand the intricacies of legislation and regulation to ensure strong charters should Kentucky choose to go in that direction; we heard from Kentucky's Commissioner of Education, Terry Holliday who experienced charters first hand as a superintendent in North Carolina and has expressed nuanced support; and we relied heavily on the research from CREDO, the Center for Research on Educational Outcomes at Stanford University, that produced the first comprehensive study of charter school impacts on student performance in 2009 and followed with a second study in 2013.

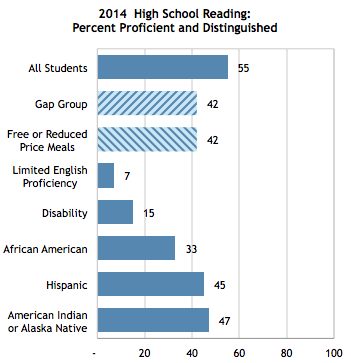

What the Committee found, in a nutshell, is that the overall performance of charters has been mixed. There are clear success stories through major charter management organizations with a longstanding track record of success, like KIPP, but the research does not currently support generic start-up charters as a clear path to higher student achievement. While the CREDO report finds that charters can be beneficial in urban settings and with African American students living in poverty, the same does not hold true for rural and suburban students. Furthermore, the need for both strong parent engagement and collaboration between all public schools within a district (including charters) were both cited in our discussions as critical indicators of overall success regardless of public charter or traditional public school.

Source: CREDO

The Committee plans to continue to study the issue with an emphasis on finding effective ways to close achievement gaps that continue to persist between groups of students. Our hope is to come up with a portfolio of tools to use in addressing Kentucky’s persistent achievement gaps.

At this point, the Committee decided to release detailed information to the public in a report entitled, “Exploring Charter Schools in Kentucky: An Informational Guide” We hope this information proves useful if policymakers continue to debate enabling legislation for charters in Kentucky. Kentucky is leading the way in many areas of education reform – and with a fair amount of success. The Prichard Committee has been committed to student progress by closing achievement gaps, ensuring strong accountability, and adequate funding for over 30 years now. It is through that same lens that the Committee now studies the issue of public charter schools.

--Stu Silberman

Correction note: This post has been revised to show the correct number of states that currently allow charter schools, with our thanks to the alert reader who identified the mistake.