Yes, they've been crossing paths this week. Through Facebook, I've been tracking a teacher-friend's efforts to find a day when her students can finish their KCCT work, including her plea, "Please Lord wait until after school to send the tornado warnings. Thanks!" They've still got sections to complete tomorrow, and I'm imagining how stressful this week has been. To all our teachers keeping Kentucky students safe and moving forward, it's time for one more heartfelt...

Thank you!

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Commitment to build

Rachel Maddow understands great work worth doing:

Of course, she's also exactly on my wavelength about doing big things. Here's how Bob Sexton and I wrote about the issue a few years ago:

That's from our 2009 paper, "Substantial and Yet Not Sufficient," written for the Education, Equity, and Law series.

Occasionally, when talking about infrastructure, Maddow will chant "wonk-a-chick-a, wonk-a-chick-a" for a while. She's on my wavelength then, too.

Of course, she's also exactly on my wavelength about doing big things. Here's how Bob Sexton and I wrote about the issue a few years ago:

A truly permanent system requires a wide array of adults who embody a muscular determination to deliver for all children. Outside of court, in the political effort to build the schools all children deserve, the definition of success should go beyond equal and adequate education for students in school today, to include creating a resilient culture of commitment.

This notion involves ideas closely related to the Brown emphasis on equality, but it adds a “Greatest Generation” emphasis on mighty achievements. To highlight the distinctive emphasis, we want to offer both imagery and words.

Visually, the commitment to educational opportunity for every child naturally summons up Norman Rockwell’s wrenching painting for “The Problem We All Live With,” showing a tiny Ruby Bridges walking to school escorted by four determined federal officials. We suggest that long-term success should summon up a few other Rockwell images. Think of his “Rosie the Riveter”, showing a young woman ready to put on coveralls, learn factory skills, and do what it takes to win a mighty war. Or think of his painting of “The Runaway,” dominated by the rather large back of a policeman who is making sure the kid in question has an ice cream soda before ensuring that he ends up at home before dark. Rosie and that policeman are Americans who mean to do what it takes. In talking about adequate schools in the political arena, it is essential to enlist millions like them. It is crucial that they see that a mighty project before them, worthy of their effort and investment, reflecting the values they most want to serve well as adults.l

Verbally, addressing a muscular commitment includes references to building, creating, nurturing, planting, and harvesting. It involves persistent language of shared effort: “our children,” “our schools,” “our state,” and “our future.” It requires a sense that mighty accomplishment is in within reach and worth the effort. It echoes President Kennedy asking what you can do for your country, or Dr. King expecting a great nation to rise up. It summons the sense of new energy and possibility that President Reagan summoned up for so many around him. It suggests that people who built Hoover Dam, defeated the Nazis, ended polio, and landed on the moon can certainly establish schools that deliver for every child.

Of course, this definition is not just about rhetoric. It is also about institutions and coalitions that can sustain stronger schools over generations.

That's from our 2009 paper, "Substantial and Yet Not Sufficient," written for the Education, Equity, and Law series.

Occasionally, when talking about infrastructure, Maddow will chant "wonk-a-chick-a, wonk-a-chick-a" for a while. She's on my wavelength then, too.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

District size: what works?

At the Daily Yonder blog (devoted to "keeping it rural"), three Ohio researchers share their analysis of research on district size:

I agree that it's an idea worth researching--while appreciating the authors' clarity that the evidence is not yet in. Both the Daily Yonder post and the full policy brief behind it are worth a read.

Maybe school consolidation “worked” for a while, but to judge from the size at which operational costs are minimized (3,000 students for an entire district and with serious inefficiencies becoming evident at 15,000 students), district consolidation has proceeded to a scale at which the claim of “working” appears hollow. (See this article in the Yonder and our full-length policy brief.)

Huge districts can work of course, but mostly they don’t work very well. The size-related odds, after all, are stacked heavily against efficiency and effectiveness. The larger the district—on average—the less favorable the odds.

Worse still, with huge size, the odds are stacked against kids, families, educators, urban neighborhoods, and rural communities. This insight is simply a logical extension of the twin literatures on the relationship of size to cost and achievement. Consolidation has probably outlived its educational and economic usefulness and is now living quite beyond its means, and possibly society’s as well.Craig Howley, Jerry Johnson, and Jennifer Petrie go on to argue that after decades of increasing district consolidation, it may be time for research to think about when deconsolidation might be a constructive step.

I agree that it's an idea worth researching--while appreciating the authors' clarity that the evidence is not yet in. Both the Daily Yonder post and the full policy brief behind it are worth a read.

Sunday, April 24, 2011

Believing in teachers, believing in students

I believe that the overwhelming majority of teachers make a positive difference in children's lives through the work they do each day.

I believe that when teachers work together to find and implement good new strategies, they can raise student results.

While I don't believe teachers can completely defeat the poverty odds and completely eliminate income-based gaps in achievement, I do believe teachers can narrow those odds and shrink those gaps. That is, I believe dedicated teachers, hunting for and applying the best available approaches, can produce better results for students from low-income families than what we see today.

At the core of my being, I believe that teaching is hard, creative, important work, entitled to our profound respect because teachers can and regularly do find ways to move children to higher levels of knowledge and skill than we once thought possible.

That's why today's big Courier-Journal education story, about how "JCPS schools search for success against poverty's stacked deck," disturbs me.

Kathryn Wallace with the NAACP does speak up for teachers being able to make a difference, suggesting strategic changes that she thinks the school system could implement to create meaningful improvement for children. Sadly, she seems to stand pretty much alone within the district.

If JCPS superintendent Shelley Berman believes teachers can change results for students, I can't tell it by reading the article.

If JCTA president Brent McKim believes teachers working collectively can lift children to better futures, I can't tell that from his comments to the newspaper.

If Terry Brooks of Kentucky Youth Advocates thinks there's a way (other than an unlikely economic revolution) for schools to do deliver more for Jefferson County children, his belief isn't visible either.

Can we do better than this?

Can we agree that poverty makes learning harder and that teachers can find ways to make learning easier?

Can we say that raising results for children from low income homes takes extra work and say that the work is worth doing?

Can we reason together and conclude both that current NCLB targets are unreasonable and that some other set of improvement targets is worth setting and striving for?

I hope so.

I believe the children of Jefferson County and every other Kentucky district are capable of learning at higher levels.

I believe just as strongly that the teachers of Jefferson County and every other Kentucky district can convert that learning potential into real, worthwhile, demonstrably higher levels of student achievement.

I believe that when teachers work together to find and implement good new strategies, they can raise student results.

While I don't believe teachers can completely defeat the poverty odds and completely eliminate income-based gaps in achievement, I do believe teachers can narrow those odds and shrink those gaps. That is, I believe dedicated teachers, hunting for and applying the best available approaches, can produce better results for students from low-income families than what we see today.

At the core of my being, I believe that teaching is hard, creative, important work, entitled to our profound respect because teachers can and regularly do find ways to move children to higher levels of knowledge and skill than we once thought possible.

That's why today's big Courier-Journal education story, about how "JCPS schools search for success against poverty's stacked deck," disturbs me.

Kathryn Wallace with the NAACP does speak up for teachers being able to make a difference, suggesting strategic changes that she thinks the school system could implement to create meaningful improvement for children. Sadly, she seems to stand pretty much alone within the district.

If JCPS superintendent Shelley Berman believes teachers can change results for students, I can't tell it by reading the article.

If JCTA president Brent McKim believes teachers working collectively can lift children to better futures, I can't tell that from his comments to the newspaper.

If Terry Brooks of Kentucky Youth Advocates thinks there's a way (other than an unlikely economic revolution) for schools to do deliver more for Jefferson County children, his belief isn't visible either.

Can we do better than this?

Can we agree that poverty makes learning harder and that teachers can find ways to make learning easier?

Can we say that raising results for children from low income homes takes extra work and say that the work is worth doing?

Can we reason together and conclude both that current NCLB targets are unreasonable and that some other set of improvement targets is worth setting and striving for?

I hope so.

I believe the children of Jefferson County and every other Kentucky district are capable of learning at higher levels.

I believe just as strongly that the teachers of Jefferson County and every other Kentucky district can convert that learning potential into real, worthwhile, demonstrably higher levels of student achievement.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Ending to begin

My youngest child has told me the substance of the last question on the last page of the last Kentucky Core Content Test he will ever take--and I like the substance of his answer. (I'll be good and not repeat what he told me while testing is still underway.)

He'll be in the class of 2012, the group we originally set out to make proficient as measured by the KIRIS assessment. Next fall, we'll know how close we got to delivering for that group in reading, mathematics, science, social studies, and on-demand writing. For the class of 2014, our target group since the 1999 start of CATS testing, we'll never know which of those goals we hit or missed.

For the coming classes, Kentucky has committed to higher standards, and our future assessments will be even more demanding. That's a good thing, and a hard thing worth the effort it's going to take.

And yet, for me, it is the moment of generational transition. From the day the 1990 Senate Education Committee marked up HB 940, later known as the Kentucky Education Reform Act, I've known this work was about my children. I read about KERA the next day, sitting in a Louisville hotel room, with a baby daughter in my arms, a toddler daughter playing a few feet away, and plans to spend the next day hunting for a home in Danville.

That chapter closed yesterday, as my Joe finished his last open-response answer and turned the page.

Naturally, new chapters open all the time. From Facebook, I know that Beau and I have at least three new "grand-students"on the way, and my neighborhood has launched a small baby-boom in the last couple of years. For their futures and thousands of others of precious Kentucky children, our new push to college-and-career-ready standards, preferably measured by challenging new multi-state assessments, will be essential. If anything, I've got more energy for the struggle now than I had when mothering was an immediate, minute-to-minute part of my life. I plan to be right in the middle of the fray, working to make the new goals reality.

And yet, though every mother knows the transitions are coming, I doubt any mom has figured out how to take the major milestones in stride. For two decades, I've been able to take in my hopes for all children and for my own three in a single glance. Now I've got to learn to adjust my vision for two separate tasks. It took me several days to get used to bifocal glasses, and this new way of thinking seems likely to take me substantially longer to absorb.

He'll be in the class of 2012, the group we originally set out to make proficient as measured by the KIRIS assessment. Next fall, we'll know how close we got to delivering for that group in reading, mathematics, science, social studies, and on-demand writing. For the class of 2014, our target group since the 1999 start of CATS testing, we'll never know which of those goals we hit or missed.

For the coming classes, Kentucky has committed to higher standards, and our future assessments will be even more demanding. That's a good thing, and a hard thing worth the effort it's going to take.

And yet, for me, it is the moment of generational transition. From the day the 1990 Senate Education Committee marked up HB 940, later known as the Kentucky Education Reform Act, I've known this work was about my children. I read about KERA the next day, sitting in a Louisville hotel room, with a baby daughter in my arms, a toddler daughter playing a few feet away, and plans to spend the next day hunting for a home in Danville.

That chapter closed yesterday, as my Joe finished his last open-response answer and turned the page.

Naturally, new chapters open all the time. From Facebook, I know that Beau and I have at least three new "grand-students"on the way, and my neighborhood has launched a small baby-boom in the last couple of years. For their futures and thousands of others of precious Kentucky children, our new push to college-and-career-ready standards, preferably measured by challenging new multi-state assessments, will be essential. If anything, I've got more energy for the struggle now than I had when mothering was an immediate, minute-to-minute part of my life. I plan to be right in the middle of the fray, working to make the new goals reality.

And yet, though every mother knows the transitions are coming, I doubt any mom has figured out how to take the major milestones in stride. For two decades, I've been able to take in my hopes for all children and for my own three in a single glance. Now I've got to learn to adjust my vision for two separate tasks. It took me several days to get used to bifocal glasses, and this new way of thinking seems likely to take me substantially longer to absorb.

Harder learning can be deeper learning

“For a teacher trying to design an assignment, the ideal thing is to put your students in a situation where they are challenged. The more someone struggles with something, the more they are going to learn,” Mr. Kornell said. “You want them to eventually feel something is easy to process, but only because they’ve worked through it and made it their own, not because you made it easy for them.”

That’s from a great new EdWeek article on research showing that, though people think they will remember content best if it seems easy to understand from the beginning, people are wrong about that. What really work is spending some time wrestling with something challenging.

For example, students think that studying short vocabulary lists of 5 to 7 words will work best, but research shows that struggling with a list of 30 words actually builds better memory. It's harder work at the time, but the effort means the information is more deeply mastered.

“Desirable difficulties” is a helpful way of describing the challenging work that makes knowledge memorable, shared in the article by Robert Bjork, director of UCLA’s Learning and Forgetting Lab.

Reading, my mind kept offering the image of Gerber baby food. It's carefully cooked, mashed, and strained to be easy on new eaters, but if we kept giving our children the soft stuff, they'd never learn to handle regular food on their own. This research seems to me to argue that it is really important for students to start "chewing" information independently.

For more on this powerful insight, check out the full EdWeek report here.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

SB 1: End-of-course tests likely to count toward student grades (Update)

Scores on state high school tests may soon count toward individual student grades, based on a vote by the Kentucky Board of Education last Wednesday.

In implementing 2009's Senate Bill 1, Kentucky will use end-of-course tests as our method for assessing high school students' reading, mathematics, science, and social studies learning, with new testing slated to begin a little over a year from now, in the spring of 2012.

Last week, KBE voted on an accountability regulation that included this new language:

A few thoughts.

First, this is not a mandate. Schools and districts are not required to count end-of-course tests as 2025 percent of each student's grade. Instead, they're required to do that or explain to the Commissioner why not. Local officials are still making the choice, even if they have to give reasons for it at the state level.

Second, the subjects to be tested are not named in the regulation. English II, Algebra II, Biology, and U.S. History are likely contenders, since KDE sought vendor proposals for tests of those courses. However, KDE appears to be keeping its option open to either add or subtract from that list.

Third, advocates for students with disabilities and limited English may have concerns about this provision. It can be harder to arrange accommodations on this sort of standardized test. I hope PrichBlog's regular readers will share what they've heard about inclusion issues in the comments.

Finally, using end-of-course scores this way responds to recurring concerns that high school students do not value and focus on state testing because they do not have "skin in the game." Making the scores part of their grades will certainly give students a personal stake in the testing results.

In implementing 2009's Senate Bill 1, Kentucky will use end-of-course tests as our method for assessing high school students' reading, mathematics, science, and social studies learning, with new testing slated to begin a little over a year from now, in the spring of 2012.

Last week, KBE voted on an accountability regulation that included this new language:

End of course test results may be used for a percentage of a student’s final grade in the course. If the district or school council’s policies do not include end of course grades in the grading policy or if the end of course grade percentage is less than twenty-five percent (25%), the district shall submit an annual report to the Commissioner showing justification for not using end of course exams for at least twenty-five percent (25%) of a student’s final grade in the course. The report shall be submitted to the Commissioner on or before December 31.[Update: My colleague Robyn Oatley reports that before the vote, the Board replaced the 25 percent above with 20 percent.]

A few thoughts.

First, this is not a mandate. Schools and districts are not required to count end-of-course tests as 20

Second, the subjects to be tested are not named in the regulation. English II, Algebra II, Biology, and U.S. History are likely contenders, since KDE sought vendor proposals for tests of those courses. However, KDE appears to be keeping its option open to either add or subtract from that list.

Third, advocates for students with disabilities and limited English may have concerns about this provision. It can be harder to arrange accommodations on this sort of standardized test. I hope PrichBlog's regular readers will share what they've heard about inclusion issues in the comments.

Finally, using end-of-course scores this way responds to recurring concerns that high school students do not value and focus on state testing because they do not have "skin in the game." Making the scores part of their grades will certainly give students a personal stake in the testing results.

Monday, April 18, 2011

SB 1 action: Accountability formula

Last Wednesday, the Kentucky Board of Education took a big step forward on the accountability element of Senate Bill 1, approving a formula for the "Next-Generations Learners component of Kentucky’s accountability system." That new formula uses scores from the new assessment system that start in 2012, with slight variations by level of school.

The elementary version combines:

The elementary version combines:

- Overall achievement in reading, mathematics, science, social studies and writing

- Gap group achievement, combining results for students with disabilities, students from low-income households, African-American students, and Hispanic students

- Individual student growth, measured as the percent of students making typical or high growth in reading and in mathematics from one year to the next

- Overall achievement (like elementary)

- Gap group achievement (like elementary)

- Individual student growth (like elementary)

- College readiness defined as percent reaching Reading, English and Mathematics benchmark scores set by ACT, Inc., on the eighth grade Explore test

- Overall achievement on end-of-course tests in key subjects

- Gap group achievement

- Individual student growth

- College readiness defined as percent reaching ACT Reading, English and Mathematics benchmark scores set by Kentucky's Council on Postsecondary education or showing readiness on another approved measure

- Graduation rate

Under Kentucky rules for creating a new regulation, there are some further steps before this formula becomes final. So, count this approach as very likely to be the system Kentucky will use next year, but not as fully settled just yet.

It's worth mentioning two more decisions that lie ahead. The scores described above will be used to rate schools as distinguished, proficient, needs improvement, or persistently low performing, but the numbers that go with each level will not be decided until next year. Similarly, the consequences that will go with those ratings are still under discussion.

Source note: The proposed regulation is 703 KAR 5:200, and you can download the full text approved by KBE here.

It's worth mentioning two more decisions that lie ahead. The scores described above will be used to rate schools as distinguished, proficient, needs improvement, or persistently low performing, but the numbers that go with each level will not be decided until next year. Similarly, the consequences that will go with those ratings are still under discussion.

Source note: The proposed regulation is 703 KAR 5:200, and you can download the full text approved by KBE here.

Sunday, April 17, 2011

SB 1: Pieces falling into place

2009's Senate Bill 1 called for Kentucky to launch new standards, assessments, and accountability provisions during the 2011-12 school year. With those deadlines now getting close, last week saw several key elements move forward. My post earlier today mentioned the choice of a vendor for key parts of the assessment system. Later this week, I'll also share a summary of the new edition of the accountability formula that will use those tests and some developments around end-of-course-testing. The news is just complex enough that I'm going to split it over several days, rather than pile it on all at once.

SB 1: Testing contractor!

In the spring of 2012, Kentucky's main assessment for grades 3 through 8 will be created by NCS Pearson, Inc. That testing will "provide blended criterion-referenced and norm-referenced tests in reading, mathematics, science, social studies and writing." Pearson will also provide Kentucky with writing on-demand tests for high schools, according to this press release from the Kentucky Department of Education.

This step is another piece of implementing 2009's Senate Bill 1 changes to standards, assessments, accountability, teacher preparation, and professional development. State testing for 2012 and beyond will also include new end-of-course tests for high school students and continued use of the Explore, Plan, and ACT tests of college readiness. The end-of-course vendor has not yet been announced.

Pearson is a major name in testing, billing itself as "the global leader in education and education technology."

This step is another piece of implementing 2009's Senate Bill 1 changes to standards, assessments, accountability, teacher preparation, and professional development. State testing for 2012 and beyond will also include new end-of-course tests for high school students and continued use of the Explore, Plan, and ACT tests of college readiness. The end-of-course vendor has not yet been announced.

Pearson is a major name in testing, billing itself as "the global leader in education and education technology."

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Now and forevermore

150 years ago, today, the flag pictured above was taken down from Fort Sumter. 146 years ago today, it flew again over that same fort. On that second occasion, Henry Ward Beecher offered these words:

On this solemn and joyful day, we again lift to the breeze our fathers’ flag, now, again, the banner of the United States, with the fervent prayer that God would crown it with honor, protect it from treason, and send it down to our children.... Terrible in battle, may it be beneficent in peace [and] as long as the sun endures, or the stars, may it wave over a nation neither enslaved nor enslaving.... We lift up our banner, and dedicate it to peace, Union, and liberty, now and forevermore.When we speak of our public schools as developing citizens, I see no choice but to be clear that we mean to nurture citizens devoted to the republic symbolized by that flag, rightly describes as one nation under God, as indivisible, and with liberty and justice for all.

Monday, April 11, 2011

Getting it right

Inclusion for students with significant differences has been one of the mighty education revolutions of my lifetime, with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requiring us to learn with and from our neighbors even when it takes some added effort to begin understanding one another.

For folks in Danville, Kentucky, one of the great gifts of that kind of inclusion has been getting to know Bruce Caudill. Bruce has autism, and this reporting in the Advocate-Messenger shares a bit of his story.

At 21, Bruce is just slightly younger than my middle daughter, so I've been in the "audience" for much of his life, and also in the literal audience for a number of his drum solos. On school council committees and in Sunday School curriculum discussions, I've listened as teachers tested ideas by thinking about how they would work for "a kid like Bruce." Since the Hub Coffee House where Bruce works is my favorite hangout, I'm very glad that he's now there to help handle the lunchtime rush.

Bruce has proven that he and we can get good things done together. Since the 1970's, teachers and students have been making that same discovery about differences that need not divide, and we should count that as a great good thing.

For folks in Danville, Kentucky, one of the great gifts of that kind of inclusion has been getting to know Bruce Caudill. Bruce has autism, and this reporting in the Advocate-Messenger shares a bit of his story.

At 21, Bruce is just slightly younger than my middle daughter, so I've been in the "audience" for much of his life, and also in the literal audience for a number of his drum solos. On school council committees and in Sunday School curriculum discussions, I've listened as teachers tested ideas by thinking about how they would work for "a kid like Bruce." Since the Hub Coffee House where Bruce works is my favorite hangout, I'm very glad that he's now there to help handle the lunchtime rush.

Bruce has proven that he and we can get good things done together. Since the 1970's, teachers and students have been making that same discovery about differences that need not divide, and we should count that as a great good thing.

Do college remedial courses matter?

Gatekeeper courses are the key early college classes students must pass to be on their way to a diploma. The normal theory is that students with weak scores –designated as not college-ready– need to be assigned to non-credit developmental courses first in order to get the skills for that credit-bearing work later. But here's a stunning slide from a Complete College America webinar presentation that suggests that we may want to probe that theory a lot harder.

The red bar shows students who were labeled "not college-ready" being just about likely to pass the gatekeeper courses without the developmental courses as with them, and also shows only small differences in passing rates for the "ready" and the "not ready" groups.

The graph doesn't give its data source, so even though I admire the Complete College effort, I'm not about to call it proof of a problem. Instead, I'll call it evidence that we should ask for evidence.

In Kentucky, how does this work? What's our evidence that taking our developmental courses makes students more likely to succeed? Could students spend less and learn as much without the developmental programs? Do programs at some schools deliver much stronger results than at others?

I haven't yet gone hunting for our in-state evidence, so I'll have to report back on what I can find in the days ahead. Kentucky numbers might be like this, or better, or worse. If anyone already has copies of relevant reports, I'll be grateful for tips and shortcuts.

For now, I'll leave the questions on the table: Do college developmental courses matter? And how do we know?

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

Common Core: moving in Maine, settled in Kentucky

Maine's governor has signed the documents to complete state adoption of the Common Core Standards, and EdWeek's Catherine Gewertz updates her wonderful map to show 44 states and the District of Columbia on board, with Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, NevadaNebraska, Texas, and Virginia (plus Minnesota on math only) still charting an independent course.

Of course, many of these states are in the very earliest phases of thinking through implementation. For example, in planning the next phase of professional development for the Gates literacy initiative, the outline for nationwide use starts with "Introduction to the Common Core."

What are Kentuckians to do when they come across the idea of "introducing" Common Core sometime next year? Open bragging on our teachers would be impolite, but our schools are really are already investing deeply in understanding and implementing the new standards. Considering how far we've come and how fast we're pushing ahead, I think we're each allowed a small, quiet, happy nod of pride. Maybe two.

Of course, many of these states are in the very earliest phases of thinking through implementation. For example, in planning the next phase of professional development for the Gates literacy initiative, the outline for nationwide use starts with "Introduction to the Common Core."

What are Kentuckians to do when they come across the idea of "introducing" Common Core sometime next year? Open bragging on our teachers would be impolite, but our schools are really are already investing deeply in understanding and implementing the new standards. Considering how far we've come and how fast we're pushing ahead, I think we're each allowed a small, quiet, happy nod of pride. Maybe two.

Monday, April 4, 2011

School-aged Kentuckians: Some trends

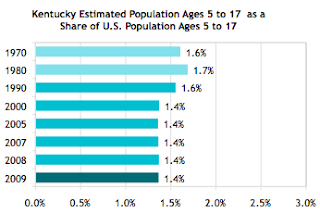

Kentucky's population ages 5 to 17 has been fairly stable over the last decade – after an impressive drop from earlier Baby Boom years. The 2010 NCES Digest of Education Statistics provides numbers from Census Bureau and Commerce Department reporting:

Our school-aged residents are now a smaller proportion of our total resident population of all ages than they were in decades past.

Finally, our school-aged group is now a smaller portion of the national estimate of children aged 5 to 17.

Our school-aged residents are now a smaller proportion of our total resident population of all ages than they were in decades past.

Finally, our school-aged group is now a smaller portion of the national estimate of children aged 5 to 17.

Early college successes stories!

Here's a national follow-up to Saturday's post on Kentucky college-in-high-school options. The Early College High School Initiative, launched in 2002 as a Jobs for the Future effort, reports that:

Since then, 230 schools across 28 states have joined to serve nearly 50,000 students each year. They are predominately young people of color. Many are from low-income families, and few of their parents have attended college. Despite these facts, they have achieved remarkable results:

• 92% of students graduate from high school (compared to the national rate of 69%)

• 86% of graduates enroll in college immediately after high school

• 78% of graduates earn at least some college credits

• 44% of graduates earn more than a year of college credits

• 24% of graduates earn 2 years of college credit or an Associate’s degreeFour new reports issued in March –also from JFF– enrich the story:

- Early College Graduates: Adapting, Thriving, and Leading in College

- Unconventional Wisdom: A Profile of the Graduates of Early College High School

- Making the Grade: Texas Early College High Schools Prepare Students for College

- Accelerating College Readiness: Lessons from North Carolina's Innovator Early Colleges

Sunday, April 3, 2011

Literacy insights from Kentucky teachers

The Literacy Design Collaborative is a strategy for implementing the Common Core Standards, currently being implemented by small groups of teachers in Boyle, Daviess, Fayette, Jessamine, Kenton, and Rockcastle schools. I learned a lot from those educators last week, including these insights:

- "Argumentation" tasks may engage students more quickly than the "informational and explanatory versions." The early implementers started with the informational version, but found that on a second round, students found the idea of taking on issue debate appealing. One wise administrator did point out, though, that students must get the information right on the way to making their arguments.

- To create strong science tasks, teachers need strong science texts that work for students with varying levels of reading proficiency--and those can be hard to find. That said, we heard about impressive tasks requiring students to martial arguments around health risks from cell phones, climate change, and use of chemical fertilizers.

- Pulling evidence and quotations from the assigned reading texts is a challenge for participating students. To me, it sounds like a good challenge –something students should be asked to do often on their way to becoming skilled before they finish high school.

- Struggling students are succeeding with these challenging tasks. The LDC strategy calls for teachers to make intentional choices in the reading selections for students, including being willing to start with varied assignments for students with varied needs as a way to build toward success for all with demanding texts at or above the grade-levels specified by the Common Core State Standards. (My very favorite parts of the day had teachers telling about students rising to levels of rigor they thought were out of reach.)

I continue to be very excited by this work, organized by the Prichard Committee under a grant from the Gates Foundation, and by the planning underway for statewide implementation under a Gates grant to the Kentucky Department of Education.

Saturday, April 2, 2011

College during high school: an idea on a roll

Around the state, students have a growing number of ways to seek both high school and college credit from the same course, on the way to earning a traditional diploma while getting a jump-start on a degree. I'm not confident I understand how different places are using the terms"early college" and "middle college," but I'm certain that the list below shows an important trend.

- In Jefferson County, "early college at Western High School is an innovative program in partnership between JCTC and JCPS. Early college is a unique and bold step in education reform. The goal of early college is based on the principal that increased academic rigor, combined with the opportunity to save time and money is a powerful motivator for students to work hard and meet challenging educational goals."

- In Fayette County, "Opportunity Middle College is a partnership between our school district and Bluegrass Community & Technical College that gives juniors and seniors a chance to take college classes while earning their high school diplomas.... This program is open to underserved youth, including low-income and first-generation college students. It is housed on the community college's Leestown campus, where FCPS students take regular high school classes taught by district staff and take college courses, too."

- In Madison County, "sixty current sophomores will be selected to participate in middle college as juniors during the 2011-12 school year. They will attend classes at Eastern Kentucky University, where they will take core high school classes while earning six college credits." [Richmond Register]

- "Western Kentucky University houses the Carol Martin Gatton Academy of Mathematics and Science in Kentucky. The mission is to offer a residential program for bright, highly motivated Kentucky high school students who have demonstrated interest in pursuing careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics... Taking courses offered by WKU, their classmates are fellow Gatton Academy students and WKU undergraduate students. At the end of two years, Gatton Academy students will have earned sixty college credit hours in addition to completing high school."

- In Franklin County, "starting this fall, 65 incoming freshmen at each school will have a chance to take an accelerated curriculum. If they pass national exams, they could start taking college courses by junior year... Teachers with the proper certification – a master’s degree and 18 hours in their subject area – could teach college-level classes at the high school. KSU and other universities have offered to train them, Buecker said. Students could also take classes on the KSU campus or online." [State Journal]

- At Owensboro Community & Technical College, "Discover College is a collaborative program between regional high schools, area home school associations, and OCTC providing students the opportunity to earn college credit while still in high school."

- "The Commonwealth Middle College located on the campus of West Kentucky Community & Technical College allows students with a good attendance record, a strong work ethic, and a 2.5 GPA or higher to take core high school courses, receive their high school diploma, and earn college credit at the same time."

- In Crittenden County, "local 11th and 12th graders now have an opportunity to take college courses at the high school during the normal school day. Thanks to a partnership between Crittenden County High School and Madisonville Community College, CCHS will be offering a college course, Fundamentals of Learning, starting in January. The course is open to all juniors and seniors, giving them an opportunity to acquire a portion of their freshman credits before going to college." [Crittenden Press]

- At Asbury, "Asbury Academy is an “Early Access to College” program for high school seniors. This program provides opportunities for high school seniors to take general education requirements at the college level (100- and 200-level courses), enabling them to complete their senior year of high school and earn college credit through dual enrollment."

(I'll be delighted if readers alert me to some further options I've missed. This is the result of a quick search, and there could easily be additional possibilities up and running or getting set to launch this fall.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)